The day the ‘Conservation Heroes’ vanished in the lap of nature

14 years ago, a terrible and unbelievable incident took place in the scenic Kanchanjunga Conservation Area in far east Nepal, which pinches me often. I was not present there at the time of occurrence, but I have a deep connection with the incident.

I am not linked to the region only because of the aforementioned incident; I have an emotional attachment with the whole Kanchanjunga Conservation Area. There are some reasons, of course.

First – I was appointed for the establishment and operation of the project by Mingma Norbu Sherpa, who was then the residential representative of World Wild Fund for Nature (WWF) for Nepal. Second – my intimacy with the community of that region and the geniality they showed at my farewell. Third – the pain I felt at the sudden demise of my mentors immediately after the conservation area was handed over to the community.

The incumbent residential representative of WWF for Nepal Dr Ghanashyam Gurung and I were chosen for the project by Mingma Norbu Sherpa. We had taken our responsibilities of the conservation of the Kanchanjunga area the same day.

We were directed by the core objective to boost the living standards of the local people of that area who were facing the challenges of harsh geographical, social and economic condition and handing the conservation area over to them eventually. Mingma Norbu Sherpa had finished his tenure by then and begun a new inning at the WWF in USA. Dr Chandra Gurung had acquired the responsibility as the residential representative of WWF after him.

In the program organized to hand over the conservation area to the community, Mingma sir had also arrived from the US. “How are you?” he asked me, entering from the gate.

I had met Mingma sir a few months earlier at WWF in Washington DC on my visit to the US in an official purpose. We had lunched together. I had appeared for a job interview in the US and he had asked how the interview had gone.

The then residential representative of the WWF for Nepal, Dr Chandra Gurung, called me on September 22, 2006 and invited for a discussion at the office. It was decided that he would attend a meeting in Chitwan the next day and head for the handover program in Taplejung.

I was working as a program administrator then. Dr Gurung had called the then Conservation Director Anil Manandhar too. Dr Gurung briefed us about the program at the Panda Meeting Hall. He drew the helicopter route on the white board and made us note the program schedule informing about the Nepali and foreign conservationist who were traveling to Taplejung. Dr Gurung was a well-organized and far-sighted personality. “This visit is not as simple as it seems. Anything might happen …. Anil and Sunil should monitor our visit,” he said.

Dr Gurung was very busy meeting and making arrangements for the foreign donors who had arrived for the handover program. After discussing upon some internal affairs, we parted with Dr Gurung and returned to our homes.

The next day, Anilji and I reached the office and, after our daily coffee, started monitoring the visiting team. My job responsibility involved dealing with crisis management and project management and maintaining a good repute with the donors, because of which I had to be in contact with Dr Gurung and other colleagues regularly.

On Saturday, the helicopter flew to Chitwan. From there it went to Bhojpur, picked Minister Gopal Rai and then reached Taplejung. Among others, the then program director and incumbent residential representative of WWF for Nepal Ghanashyam Gurung, program officer Neera Shrestha, project chief Ang Chhiring Sherpa were present at Taplejung for the program.

After the conservation area was formally handed over to the community in a program at Phungling, the local people requested the guests to make a visit to Ghunsa that lay in the conservation area. The visiting team was welcomed by the locals of Ghunsa and showed their joy and gratitude.

We heard the news of the helicopter having flown towards Kathmandu. We were monitoring all details glueing ourselves to the radio communication set. It had been almost two hours that the helicopter had departed from Ghunsa, so. I contacted Ghunsa as it was time for landing. I was notified that there had been an abrupt disruption in the weather, but the helicopter had flown towards Kathmandu. Three hours passed but there was no information about the helicopter.

The airport tower notified that the contact had been lost. We tried again using the radio set but there could be no proper communication as the weather had worsened. From Phunglig, no more information than the message about the helicopter returning to Kathmandu came.

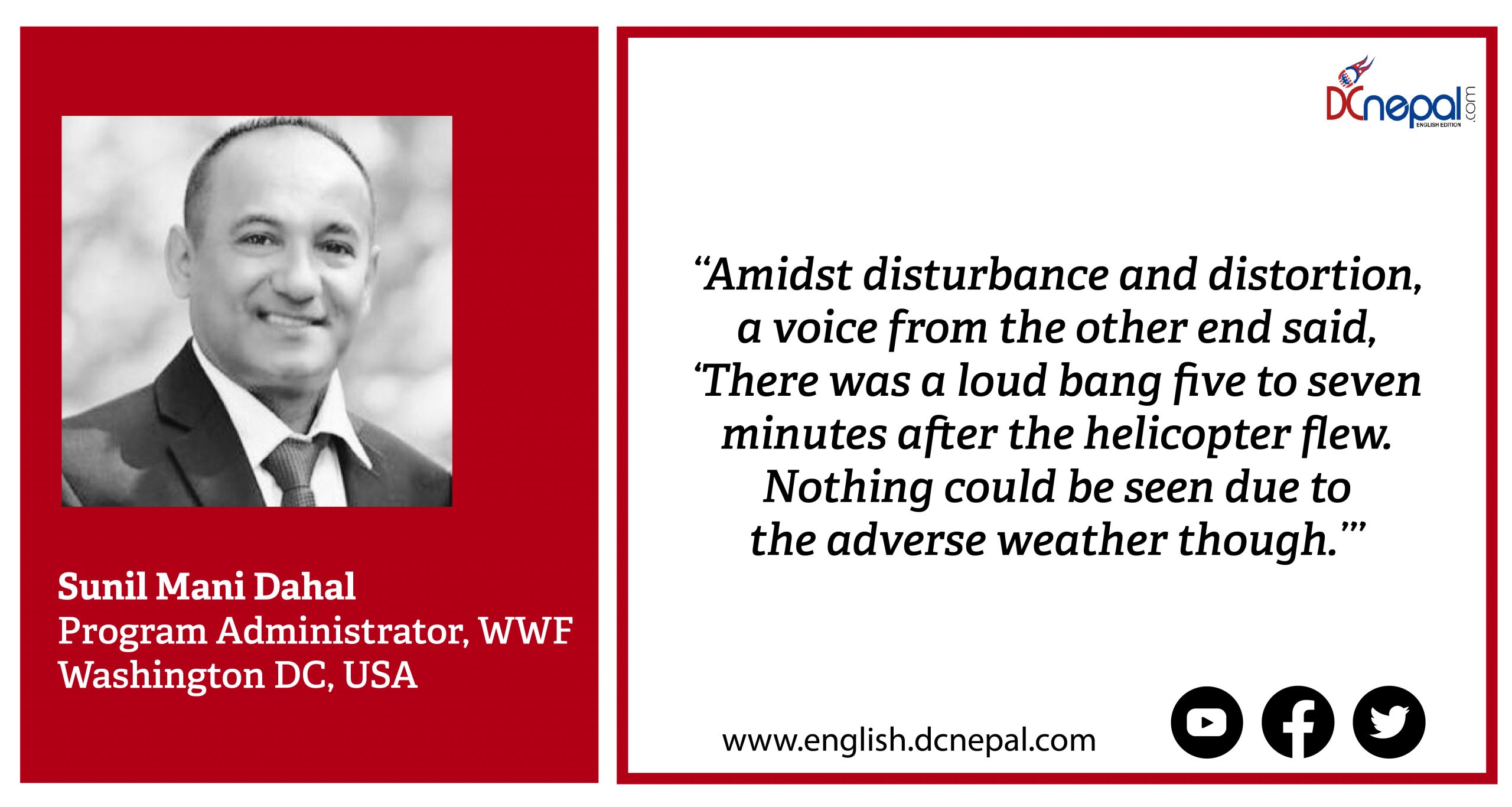

We contacted Ghunsa again after four hours. Amidst disturbance and distortion, a voice from the other end said, ‘There was a loud bang five to seven minutes after the helicopter flew. Nothing could be seen due to the adverse weather though’” This was my unclear and unsubstantiated communication with Himali Chungda.

Anilji, who was by my side, had now become completely restless and had started to move to and fro. We were both tensed as the helicopter was lost and we were trying to make calls and communicate every minute or two, which was made impossible by the unfavorable weather.

The two of us then gathered all staff. We didn’t have any proof to say that the helicopter had crashed. There was no plan to go anywhere else from there too. Eventually, we became mentally prepared for rescue and crisis management.

We unfurled the maps of the Kanchanjunga area in front of us and started the probability study. I knew the terrain of that area better than others. Study and discussions were made as to where the helicopter could have reached within five to seven minute of flight. Mountains, hills, slopes and ravines were studied carefully.

We made a rescue team without wasting time and increased our activities in search of the helicopter. I had the responsibility of monitoring the site of accident, field coordination, logistic and press briefing. We stayed at the office, ready with sleeping bags, making arrangements for the search operation.

The weather was very hostile at Taplejung. We chartered a helicopter but it had to return being unable to land. Incumbent residential representative Ghanashyam Gurung, program officer Neera Shrestha and project chief Aaang Chhiring Sherpa had provided their seats in the helicopter to the locals and were there in Taplejung.

A team under Ghanashyamji was sent to the Ghunsa region to involve the locals in the search operation. International rescue teams were also readied but the weather disturbed the search operations. The local youths organized to conserve the snow leopards were mobilized for the task.

Alas! What we feared had happened. After seven days of rigorous search, local youths found the site of accident. The helicopter was scattered in pieces, our mentors had become martyrs.

The grief of having lost 24 of the world’s best conservationists that day is indescribable. A new generation of conservationists came to the fore after that, fulfilling the saying “Conservation cannot wait.” However, the absence of decades of experience and expertise shall always be felt in the field of conservation. I express my reverence and heartfelt condolence to all the ‘Conservation Heroes’.

Facebook Comment

latest Video

Trending News

- This Week

- This Month