Inclusive Exclusion- With Nepal Examples

The term “inclusive exclusion” may sound paradoxical at first glance, but it is a powerful concept used in various disciplines—particularly in political theory, sociology, philosophy, and critical theory—to describe situations where inclusion is accompanied by a simultaneous act of exclusion.

Inclusive exclusion refers to a process by which certain individuals, groups, or ideas are formally included within a system, structure, or discourse, yet are functionally marginalized, restricted, or subordinated within that same framework. They are “inside,” but on unequal or conditional terms.

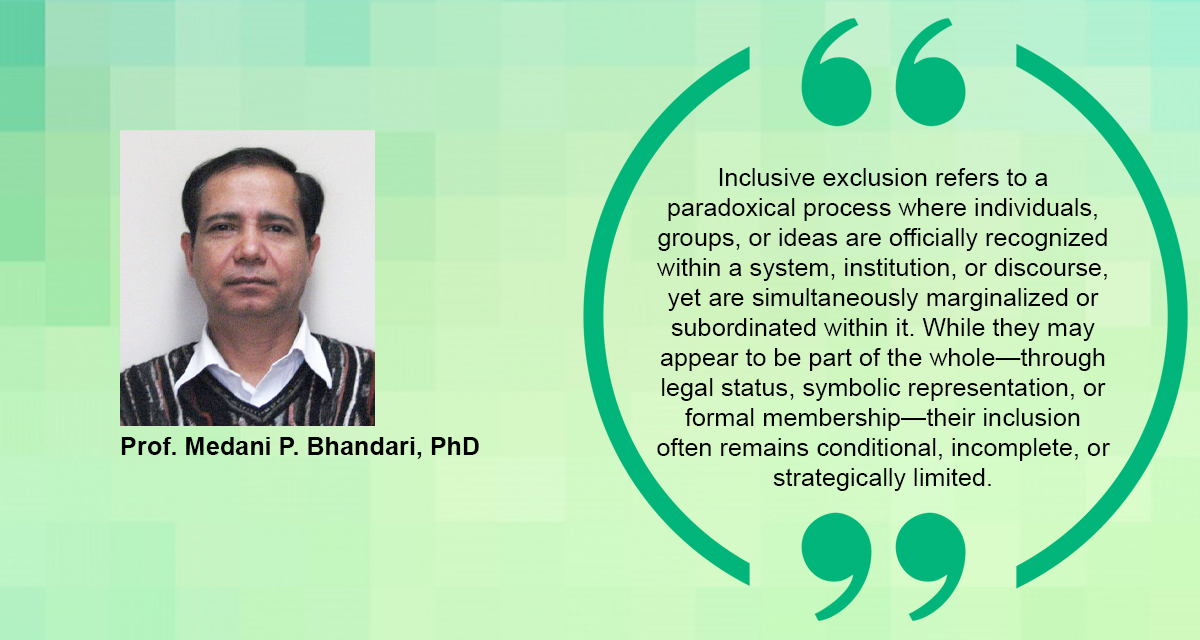

Inclusive exclusion refers to a paradoxical process where individuals, groups, or ideas are officially recognized within a system, institution, or discourse, yet are simultaneously marginalized or subordinated within it. While they may appear to be part of the whole—through legal status, symbolic representation, or formal membership—their inclusion often remains conditional, incomplete, or strategically limited. This duality allows dominant systems to project an image of openness, diversity, or fairness while continuing to maintain underlying structures of inequality and control.

This concept is evident across various contexts. In politics, marginalized communities may be granted citizenship but remain excluded from genuine political power or social acceptance. In education, minority voices may be included in curricula, but only superficially, with dominant narratives remaining unchallenged. Similarly, in workplaces, women or people from underrepresented backgrounds may be included through diversity initiatives but often find their roles restricted to symbolic representation or subjected to conformity pressures that suppress authentic expression.

The mechanism of inclusive exclusion operates by defining the terms of inclusion, often requiring assimilation into the dominant culture or ideology. It creates a space where those included are visible yet voiceless, present but powerless. Their inclusion does not lead to equity or empowerment but serves to reinforce the status quo by neutralizing dissent and masking exclusionary practices.

Understanding inclusive exclusion is essential in critiquing liberal democratic frameworks, institutional diversity efforts, and reformist approaches that fail to address deeper structural inequalities. It challenges us to ask whether inclusion efforts are genuinely transformative or simply cosmetic—serving to preserve existing hierarchies under the guise of progress. True inclusion requires more than presence; it demands agency, voice, and a restructuring of the terms by which individuals and groups are recognized, valued, and empowered within systems of power and knowledge.

Key Characteristics:

Apparent Inclusion, Actual Marginalization

While a person or group may be recognized or granted formal membership, rights, or participation (e.g., citizenship, access to institutions), their inclusion is limited, conditional, or symbolic—maintaining unequal power dynamics.

Apparent Inclusion, Actual Marginalization refers to a situation where individuals or groups are formally recognized within a system—such as through legal citizenship, institutional access, or symbolic representation—but their presence does not translate into real power, influence, or equitable treatment. Instead, their inclusion remains superficial, constrained by underlying structures that perpetuate inequality. This creates a dissonance between visibility and agency, where being “included” masks ongoing exclusion.

For example, in many democratic societies, minority groups may have the right to vote, run for office, or access public services. However, systemic barriers—such as economic inequality, racial discrimination, language barriers, or cultural biases—limit their ability to fully participate or benefit from these rights. Their formal inclusion serves to legitimize the system, giving the impression of fairness and equality, while their lived experiences reflect marginalization and limited access to resources and decision-making power.

Similarly, in the workplace or academia, diversity and inclusion initiatives may appear to embrace representation from different backgrounds. Yet, if organizational cultures remain hostile, if leadership roles are inaccessible, or if dominant norms are not challenged, then the inclusion is largely symbolic. Those included must often conform to existing frameworks, and their perspectives may be sidelined or dismissed.

This form of marginalization is particularly insidious because it is often hidden behind the language of progress and equality. It maintains unequal power dynamics by offering limited space for difference, dissent, or transformation. Rather than dismantling exclusionary practices, apparent inclusion allows them to persist under a veneer of inclusivity. Recognizing this dynamic is crucial for advocating genuine inclusion—where individuals and groups are not only present but also empowered, heard, and given equal opportunities to shape and benefit from the systems they are part of.

Structural Mechanism

Inclusive exclusion often works at a systemic level, reinforcing hierarchies, social norms, or power relations while appearing to uphold principles of equality and inclusion.

Structural Mechanism refers to how inclusive exclusion operates not just at an individual or interpersonal level, but through deeply embedded systems and institutions that maintain and reproduce inequality. These mechanisms function subtly, often under the guise of fairness, meritocracy, or progress, reinforcing dominant hierarchies and social norms while projecting an image of inclusivity and equal opportunity.

Inclusive exclusion, as a structural process, is built into the rules, policies, and cultural assumptions of organizations, governments, and societies. For instance, a university may adopt inclusive admission policies to diversify its student body, but if the curriculum, faculty demographics, campus culture, and support systems remain unrepresentative or unwelcoming to marginalized students, their inclusion is partial and conditional. The system recognizes their presence but does not transform to support their success or affirm their identities.

Similarly, legal and political frameworks may grant formal rights to minority populations—such as voting rights, access to education, or anti-discrimination protections—but without addressing the historical and structural injustices that disadvantage these groups, such rights remain performative. They are included in the system but excluded from its benefits and decision-making processes.

These mechanisms often rely on bureaucratic neutrality, colorblind policies, or standardized measures of success, which appear objective but are rooted in dominant cultural and social norms. As such, they reward conformity and penalize difference, perpetuating inequality while denying its existence.

The power of structural inclusive exclusion lies in its invisibility—it masks exclusion as inclusion, making it harder to challenge. It requires critical examination of the very foundations of institutions and systems to expose the gap between appearance and reality. To move beyond superficial inclusion, it is necessary to dismantle these structural mechanisms and replace them with frameworks that actively redistribute power, recognize difference, and promote genuine equity and justice.

Discursive Tool

It may be used rhetorically—especially in politics or policy—where the language of inclusion (e.g., diversity, human rights, representation) masks ongoing exclusionary practices.

Discursive Tool refers to the strategic use of language and rhetoric to create the appearance of inclusion while maintaining exclusionary structures. In this context, inclusive exclusion functions through carefully crafted narratives—often in political speeches, institutional policies, or public discourse—that emphasize values like diversity, equality, human rights, and representation. However, these terms are frequently employed in a way that obscures persistent marginalization and systemic injustice.

In politics, for example, governments may adopt the language of multiculturalism or gender equality while enacting policies that disproportionately harm immigrant communities or fail to address gender-based violence. The rhetoric of inclusion becomes a mask for inaction or harm, projecting progressiveness without enacting substantive change. Similarly, corporate diversity statements often highlight commitments to equity and representation, yet fail to address internal discriminatory practices or the lack of diverse leadership. This rhetorical inclusion can neutralize critique and deflect attention from deeper structural issues.

Discursively, inclusive exclusion also manifests in how marginalized groups are portrayed. They may be included in narratives as victims needing rescue, or as symbols of a tolerant society, rather than as empowered agents with their own voices and agendas. This form of representation often strips them of complexity and reinforces stereotypes, limiting their real participation in shaping discourse and policy.

Furthermore, terms like “equal opportunity” or “colorblindness” may sound inclusive but can actually erase historical and social contexts of inequality. By emphasizing sameness rather than justice, such rhetoric supports the status quo under the illusion of fairness.

As a discursive tool, inclusive exclusion thus plays a powerful role in legitimizing systems of dominance. It pacifies demands for transformation by offering symbolic recognition instead of structural change. Unmasking this rhetoric is essential for advancing genuine inclusion, where language reflects and supports meaningful action and equity.

Examples Across Contexts:

1. Political Philosophy (Agamben)

Philosopher Giorgio Agamben introduces the concept of inclusive exclusion through his theory of sovereign power, particularly in his work Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. At the heart of Agamben’s analysis is the figure of the “homo sacer”—a person who is paradoxically included within the legal system only through their exclusion from the rights and protections it offers. This individual can be killed without it being considered homicide, yet cannot be sacrificed according to religious law—marking them as both inside and outside the political and legal order.

The homo sacer embodies bare life—life reduced to its biological existence, devoid of political value or recognition. Such individuals are not entirely outside the law but are included by being placed in a zone of exception, where normal legal protections are suspended. The sovereign, according to Agamben, holds the power to decide who enters this zone—who can be stripped of rights while still being subject to control. This reveals how inclusion can be structured around exclusion: the law includes someone only by excluding them from its core protections.

Agamben applies this concept to modern political systems, showing how states often maintain control through the creation of states of exception—such as emergency laws, detention centers, or refugee camps—where people are held without trial or due process. These individuals are legally present but lack political agency, legal recourse, or recognition as full subjects.

This insight is foundational to understanding how inclusive exclusion operates in sovereign systems. It exposes how the language of legal inclusion can coexist with the denial of political subjectivity. In today’s world, migrants, stateless people, prisoners, and marginalized groups often occupy this liminal space, revealing the ongoing relevance of Agamben’s critique of modern power and the fragility of inclusion under sovereign logic.

2. Citizenship and Immigration

Migrants or marginalized ethnic groups may be granted legal citizenship (inclusion), but still face social discrimination, surveillance, or lack of political voice (exclusion). They are part of the nation-state but not fully embraced by it.

The concept of inclusive exclusion is especially visible in the realms of citizenship and immigration, where legal status does not necessarily guarantee full social, political, or cultural inclusion. Migrants, refugees, and marginalized ethnic groups may be formally recognized as citizens or legal residents—thereby included within the framework of the nation-state—but continue to face exclusion through social discrimination, systemic surveillance, limited access to rights, or political invisibility.

This dynamic reveals how citizenship can be stratified. Legal citizenship offers a sense of belonging on paper, but in practice, many individuals remain outsiders within. Their presence is tolerated but conditional; their loyalty and identity are often questioned; and their participation in the nation’s political, cultural, or economic life is restricted by both formal and informal barriers. For instance, immigrant communities may be disproportionately targeted by law enforcement or national security policies, even as they contribute meaningfully to the country’s labor force, culture, and economy.

In many democratic societies, this dual logic of inclusion and exclusion is masked by rhetoric emphasizing diversity, equality, and multiculturalism. Yet systemic racism, xenophobia, and nationalism continue to shape who is seen as a “true” citizen and who is viewed as a permanent other. Discriminatory practices in education, housing, employment, and media representation reinforce the sense that legal citizenship does not automatically lead to social acceptance or political empowerment.

This paradox undermines the foundational ideals of democratic citizenship, which presume equal participation and protection under the law. By highlighting the gap between formal inclusion and lived experience, the lens of inclusive exclusion calls for a reimagining of citizenship—one that goes beyond legal recognition to embrace social justice, equal voice, and genuine belonging for all members of a society.

3. Education Systems

Curricula may include diverse perspectives (inclusion), but the dominant narratives remain Eurocentric or patriarchal, subtly excluding non-dominant voices even as they are nominally represented.

In education systems, inclusive exclusion manifests when institutions and curricula formally incorporate diverse perspectives but continue to uphold dominant narratives, such as Eurocentrism, patriarchy, or colonial worldviews. While marginalized histories, cultures, and epistemologies may be acknowledged or included in textbooks and classrooms, their representation is often superficial, tokenistic, or framed through dominant lenses that undermine their authenticity and agency.

For example, schools may celebrate multicultural days, include authors of color in reading lists, or add gender and race modules to the curriculum. However, if the core structure of knowledge—how subjects are taught, whose voices are centered, and what is considered “legitimate” knowledge—remains unchanged, the inclusion does little to challenge the status quo. Indigenous knowledge, non-Western philosophies, and feminist perspectives may be mentioned, but they often exist on the margins of the curriculum, treated as add-ons rather than integral frameworks.

This form of inclusion maintains a subtle hierarchy of knowledge, where dominant (often Western, male, heteronormative) narratives retain authority and universality, while others are presented as particular or secondary. Teachers and students from marginalized backgrounds may find their histories distorted, minimized, or excluded, leading to feelings of alienation and erasure even within supposedly inclusive spaces.

Moreover, the structure of educational institutions—from standardized testing to language policies and classroom dynamics—often privileges students who align with dominant cultural norms. As such, those from different backgrounds may face additional barriers to success and recognition, despite being formally included in the system.

Recognizing inclusive exclusion in education requires rethinking pedagogy, curriculum design, and institutional culture. It calls for a genuine commitment to epistemic justice: not just adding diverse content, but transforming how knowledge is valued, who gets to produce it, and how power is distributed in the learning process.

4. Gender and Intersectionality

Women or gender minorities may be included in institutional structures (e.g., workplaces, academia), but only if they conform to pre-existing norms. Their presence is conditional, and their difference is tolerated rather than embraced.

In many parts of the developing world, inclusive exclusion is acutely evident in how women and gender minorities are integrated into institutional structures—such as workplaces, academia, and political systems—under conditional terms. While formal inclusion may be achieved through quotas, representation policies, or gender-sensitive development goals, deeper exclusion persists in the form of structural bias, cultural norms, and institutional inertia.

Women and gender-diverse individuals are often expected to conform to patriarchal or heteronormative expectations to be accepted. For example, a woman may hold a leadership position but must adopt dominant masculine behaviors or suppress aspects of her identity to be taken seriously. Gender minorities may face token representation without real voice or influence. Their inclusion becomes performative—used to project progress—while the underlying systems remain unchallenged.

In the workplace, women may be hired in growing numbers, yet still face wage gaps, sexual harassment, limited upward mobility, and the “double burden” of balancing paid work with unpaid caregiving responsibilities. Leadership remains male-dominated, and decision-making processes often exclude or marginalize alternative gendered perspectives. In academia, women researchers may be included but under-cited, under-funded, or directed toward “soft” subjects, reinforcing gendered divisions of knowledge.

Moreover, intersectionality intensifies exclusion. Rural women, women with disabilities, indigenous or minority women, and LGBTQ+ individuals face compounded barriers. Their social, cultural, and economic marginalization intersects, often rendering them invisible even within gender equality initiatives. Policies might address “women” in general but fail to account for the diversity of experiences and identities within that category.

Addressing inclusive exclusion in the context of gender and intersectionality in the developing world requires not only legal reforms or representation quotas, but also transformational shifts in social attitudes, institutional cultures, and resource distribution. It calls for challenging dominant norms, amplifying marginalized voices, and redefining inclusion as a space where difference is not only tolerated but celebrated and empowered.

Theoretical Implications:

Inclusive exclusion invites a profound and necessary rethinking of what genuine inclusion entails. At its core, this concept unmasks the limitations of symbolic gestures or surface-level reforms that proclaim inclusivity while leaving deeper systems of inequality intact. It urges us to move beyond the appearance of inclusion—beyond counting numbers, issuing statements, or adding diversity checkboxes—and instead interrogate the conditions and quality of that inclusion.

When individuals or groups are brought into a system only under conditional terms—forced to assimilate, silenced in their difference, or granted limited participation without influence—they remain functionally marginalized. This exposes a vital distinction: Is inclusion a mechanism for transformation, or a strategy to preserve the status quo? True inclusion requires reconfiguring the structures, norms, and power dynamics that have historically excluded people in the first place.

Inclusive exclusion poses tough but essential questions:

Does inclusion redistribute power, or merely diversify its appearance?

Are marginalized voices genuinely heard and centered, or simply present without influence?

Does the system evolve in response to inclusion, or does it absorb difference in ways that maintain dominance?

This concept challenges us to think in systemic and intersectional terms—recognizing that meaningful inclusion must dismantle hierarchies, create space for alternative ways of knowing and being, and allow marginalized identities to thrive on their own terms. It also highlights the risk of inclusion being co-opted as a tool of control—where recognition becomes a means to pacify demands for justice without addressing root causes of exclusion.

Ultimately, inclusive exclusion reminds us that inclusion without equity is insufficient, and that true belonging arises only when systems are transformed to reflect the full diversity, dignity, and agency of all people.

Why It Matters

Helps uncover hidden mechanisms of marginalization:

Inclusive exclusion provides a lens through which we can examine the subtle, often invisible dynamics that perpetuate marginalization despite the appearance of inclusion. Many systems, from education to politics, claim to be open and inclusive, yet they may still perpetuate exclusion through structural biases, unequal access, and subtle discrimination. By critically analyzing these dynamics, inclusive exclusion helps us recognize that marginalization often persists beneath the surface, even when formal policies appear to include all. This awareness is the first step toward identifying the hidden barriers that prevent true equality and equity.

Illuminates how power operates subtly within systems that claim to be open or democratic:

One of the key insights of inclusive exclusion is its ability to reveal how power operates in covert and insidious ways within systems that claim to be democratic or just. In many cases, the language of inclusion (e.g., “equal opportunity,” “diversity,” “representation”) can mask the continuation of inequitable practices. By focusing on the disconnection between legal inclusion and lived experience, inclusive exclusion helps us understand how those in power may maintain control under the guise of openness, while subtly reinforcing unequal structures. This understanding is crucial for exposing and disrupting the micro and macro levels of power that govern social, political, and economic systems.

Offers a critical tool for social justice work—pushing for inclusion that is not just symbolic, but transformative:

Inclusive exclusion is an essential tool for social justice advocacy, as it encourages a shift from symbolic gestures toward genuine, transformative inclusion. In social justice work, the aim is not merely to include marginalized groups in a superficial way but to empower them with real agency, rights, and opportunities. This framework pushes for changes that address not only the representation of marginalized groups but also the underlying structures of power, resources, and decision-making that keep them at the margins. It advocates for inclusive practices that are meaningful, not tokenistic, and calls for systemic transformation that values difference and ensures equal participation for all.

Nepal’s condition

Nepal’s condition in terms of inclusive exclusion is a complex reflection of both progress and persistent challenges. While the country has made significant strides in promoting inclusion through legal reforms, such as gender quotas, affirmative action for marginalized communities, and a new constitution that recognizes diversity, deep-rooted inequalities continue to shape the lived experiences of many individuals, particularly ethnic minorities, women, and the LGBTQ+ community.

Despite the formal inclusion of these groups within political, social, and economic systems, their real participation remains limited. In practice, marginalized communities often face discrimination, exclusion from decision-making processes, and limited access to resources. For instance, women may hold political positions due to gender quotas, yet still face systemic barriers such as patriarchal norms, violence, and unequal economic opportunities. Indigenous and Dalit communities, while included in the constitution’s provisions for affirmative action, still grapple with social stigmas, economic disparities, and lack of representation in key sectors.

Inclusive exclusion in Nepal reflects the tension between legal recognition and social reality. While the country’s legal frameworks may embody inclusive ideals, their implementation often falls short of creating true equality. This highlights the need for deeper structural change—one that goes beyond formal inclusion to address the underlying power dynamics that perpetuate inequality.

In my view, genuine inclusion in Nepal requires transformative change—one that redefines societal norms, provides equal access to resources, and ensures the full participation of all groups in shaping the country’s future. Inclusion must not be symbolic but must strive for real empowerment and justice for all, especially those at the margins.

In my opinion, inclusive exclusion exposes the disparity between the outward appearance of inclusion and the reality of marginalization. It serves as a vital tool for ensuring that social change goes beyond superficial gestures and is genuinely substantive. To me, it emphasizes the need for a more honest and profound engagement with power, pushing for real equity rather than just superficial diversity.

Thank you!

Facebook Comment

latest Video

Trending News

- This Week

- This Month