The Anthropology of Chhath Puja

Celebrated for over 3,000 years, Chhath Puja blends sun worship, fasting, water immersion, and offerings rooted in the five elements to promote physical health, mental clarity, and spiritual harmony, a living tradition of natural healing and ecological mindfulness.

27 October, Kathmandu. Chhath Puja is one of the oldest surviving Vedic festivals, celebrated across the southern belt of Nepal and parts of northern India for over three millennia. What sets it apart from other Hindu festivals is that it does not involve priests. Devotees themselves perform the rituals, following strict rules of purity, sequence, and discipline. Anthropologically, this is a significant pre-brahmanical tradition: while priest-led rituals often allow flexibility, Chhath preserves its original structure and discipline, ensuring that every participant, rich or poor, experiences the festival in the same rigorous manner. This strictness is central to its essence: it reflects personal responsibility, equality, and the unmediated connection of humans with nature and cosmic forces. At the same time, Chhath is more than spiritual devotion; it embodies a form of naturopathy, where fasting (Nirjala Barta), sun exposure, and water immersion provide tangible physiological and psychological benefits, harmonizing the body, mind, and spirit.

The origins of Chhath Puja are deeply rooted in Hindu mythology, particularly in the epic of Lord Rama. It is believed that upon returning to Ayodhya after fourteen years of exile, Rama and his wife Sita observed a fast in honor of the Sun God, expressing gratitude for the cosmic energy that protected them and guided them back home. They broke the fast only at sunset. This act of devotion and discipline became the foundation for the rituals of Chhath Puja. Over time, the festival also came to honor Chhathi Maiya, the goddess associated with the nurturing power of the Sun. Usually the Nirjala Barta and Chhath Puja are performed by the married women for the wellbeing of their husband and family. Often linking themselves with Sita, while their husbands symbolically represent Rama.

The four-day festival unfolds like a journey of purification. On the first day, Arba-Arbain (Nahaya-Khay), devotees bathe in rivers or ponds, cleansing both body and spirit. This act of immersion reaffirms the bond between humans and water, the source of life. The second day, Kharana, marks the beginning of the 36-hour Nirjala Barta, a fast without food or water. It is a test of endurance and faith, but also a form of naturopathic healing. From a scientific viewpoint, this kind of lengthier fasting activates autophagy, the body’s natural cleansing mechanism that removes damaged cells and promotes healing.

On the third day, Sandhya Arghya, devotees prepare delicacies from grains and offer prayers to the setting Sun. Standing waist-deep in water, they extend their offerings with folded hands, watching the Sun descend beyond the horizon. The act symbolizes accepting the cycle of death and rebirth, the end of a day as the beginning of new energy. This ritual’s posture, immersed in water, eyes fixed on the horizon, encourages stillness and mindfulness, bringing physical calmness and emotional clarity. Sleeping on riverbanks reinforces the festival’s egalitarian spirit: every devotee shares the same earth and air, dissolving social differences under the open sky.

The fourth day, Usha Arghya, takes place at dawn, when devotees welcome the rising Sun and offer gratitude for its life-giving energy. Sunrise and sunset, known as sandhya kaal, are considered the transitional moments when natural energies shift, and fasting allows the body to better absorb energies. Modern scientific studies have even noted that such practices can enhance focus and calmness by influencing brain wave activity. In traditional understanding, this was already known as “Surya Shakti”, the healing energy of the Sun that sustains all life. In recent decades, scientists have been showing concerns on the linkages between the calendar of Chhath and the gamma wave emissions of the Sun. Some even have been claiming that in the morning of the last day of Chhath, Karthik Shukla Saptami, is linked with the ancient tradition of planned solar exposure may stimulate brain activity linked with calmness, clarity, and healing, echoing ancient beliefs about the Sun’s curative power.

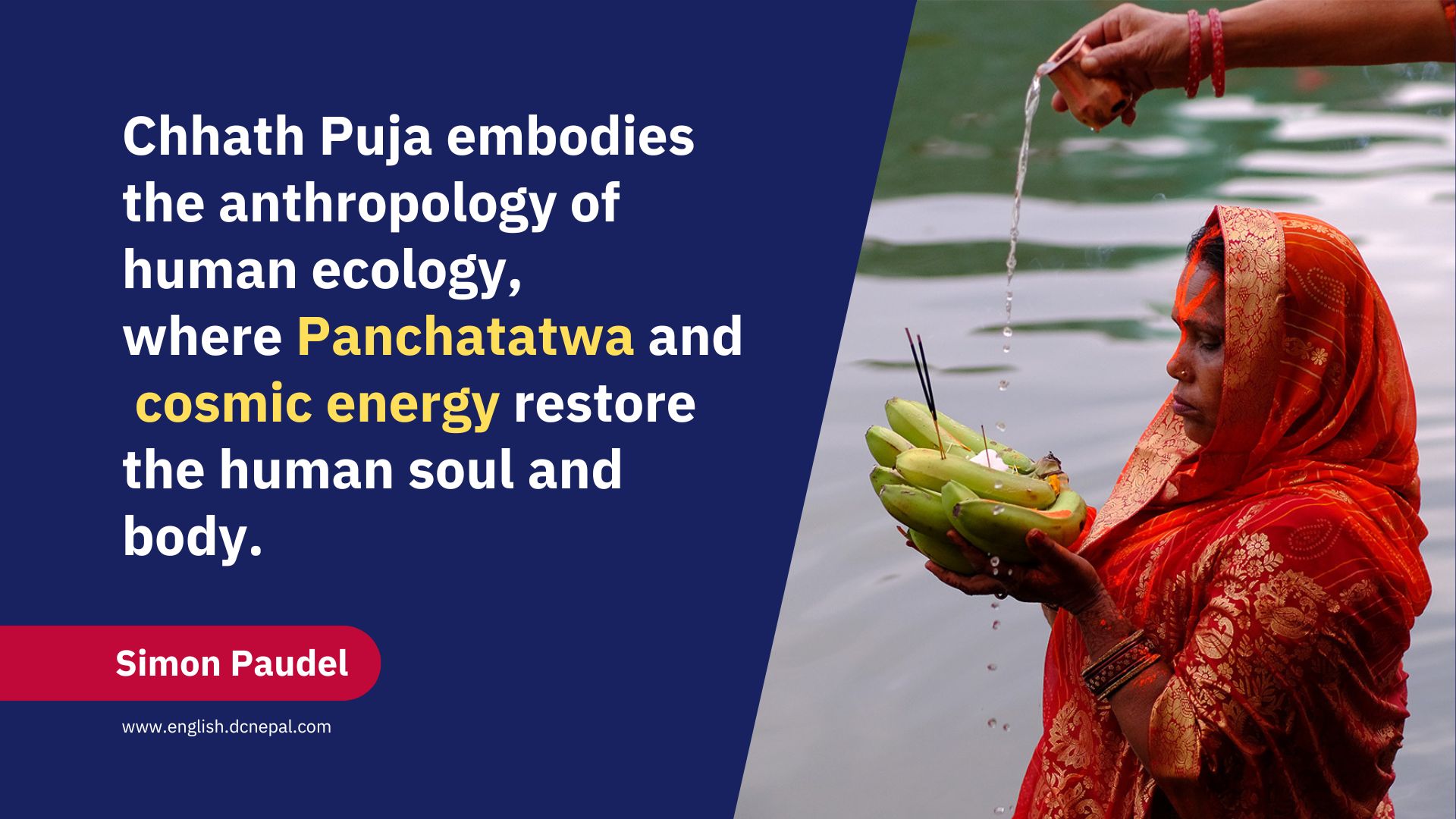

At the heart of Chhath lies the philosophy of Panchatatwa, the five elements of nature: Earth, Water, Fire, Air, and Space. Each ritual integrates these elements into a single rhythm of life. Water purifies the body and symbolizes continuity. Earth manifests in the grains, fruits, and vegetables offered during the puja, representing nourishment and gratitude. Fire is embodied by the Sun, the ultimate energy that sustains all living forms. Air circulates through the breath, which devotees regulate in silence and focus, while Space provides the setting in which all existence unfolds.

When viewed anthropologically, this elemental harmony reflects a profound ecological understanding. Chhath is not merely a ritual, it is a lived philosophy of human ecology, where balance with the environment ensures collective well-being. The fasting cleanses the body through natural detoxification; the exposure to sunlight activates vitamin synthesis and strengthens immunity; the immersion in water reduces stress and regulates temperature; and the silent meditation reconnects the mind with the rhythm of the cosmos. This alignment of body, nature, and spirit is a form of naturopathic healing, practiced long before modern medicine named it so.

The festival’s meaning extends beyond individual healing, it is also a reminder of ecological ethics. The rituals are entirely organic and self-sustained; no artificial materials, luxury items, or priestly interventions are required. Every devotee, regardless of wealth or caste, prepares offerings from homegrown produce and experiences the same physical discipline. This shared austerity transforms Chhath into a celebration of equality and humility before nature’s forces.

Though Chhath Puja remains deeply rooted in the Terai flatlands, particularly in the Mithila region, its essence has now spread across urban landscapes. In Kathmandu, sites like Kamalpokhari, Guheshwari, and Nakhu Riverbanks transform into sacred spaces each year, where migrant communities recreate their ancestral traditions amidst concrete and chaos.

Facebook Comment

latest Video

Trending News

- This Week

- This Month