Changing trends of geopolitics: The varying interests of global powers in South Asia

Kathmandu. As the eyes of the world were transfixed on the 2020 US Presidential elections, there were some trepidation as well as optimism attached with the outcome of the race. The United States of America is an important actor in the wider global politics, and it is impossible to undermine the impact of its foreign policies in the international arena. With Joe Biden having been elected as the 46th President of the US, the geopolitical landscapes are expected to shift worldwide, and South Asian cannot be an exception to it.

Overarching scenario

The Phase I of the Malabar drills have just concluded, with the members of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue or Quad, that include the US, India, Australia and Japan, participating together for the first time since 2007, in a joint naval exercise. The Royal Australian Navy, Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force, Indian Navy and the US Navy, remaining cautious of the threat posed by the global pandemic, participated in a “zero contact” highly advanced drills in the Bay of Bengal.

Alongside these deliberations, is the China element that plays into the varying interests in South Asia. Beijing has laid the groundworks for its extremely ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) within most South Asian states, excluding Bhutan and India. Regardless of the progress reports on the projects in the respective countries, China is expanding its influence throughout the region and across the state borders, and sea lanes that India considers vital for its security. The Global Times has observed the Malabar drills as a stepping stone towards forming an “Asian version of NATO,” that would seek to counter China’s rise, further asserting that “India pins high hopes on strengthening its ties with external powers like the US to impose geopolitical pressure on China in the oceans.”

The Global Times report has further cautioned that, interference “from external powers will complicate India’s choices.” India and China have been engaging in a face-off since early May, following a rapid escalation of tension at the borders. After reports surfaced that Beijing was deploying additional troops to the Line of Actual Control (LAC), Robert O’Brien, the US National Security Advisor had told India that a harder approach was necessary in its dealings with China. The involvement of an external power, especially the US, was not well received by Beijing.

Washington has, meanwhile, increased its involvement with Taipei. The rifts between Beijing and Washington rippled and widened when Donald Trump took office in 2017, and broke the standard protocol by receiving the congratulatory call of Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen, effectively infuriating China. The US had established diplomatic relations with China in 1979, by withdrawing Taiwan’s recognition, cementing the former’s place in the United Nations Security Council as one the Permanent Five members (P5).

After the US formally recognized China, moreover, it terminated the Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty (1955-1980), and adopted the long-standing policy of “strategic ambiguity.” Based on the policy, the US upheld its informal ties with Taiwan, much to the dislike of Beijing, which considers the island to be its sovereign territory.

Current dynamics, possible future

The US is involved within the affairs of the South Asian region due to a few major reasons, that includes China’s growing influence, the Quad alliance and its Indo-Pacific strategy. The report has cast India in a major role, calling it “a major defense partner,” and had highlighted the importance of the strategy by claiming that “the Indo-Pacific increasingly is confronted with a more confident and assertive China that is willing to accept friction in the pursuit of a more expansive set of political, economic, and security interests.”

With China and India engaged in a military stand-off at Eastern Ladakh, the US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo landed in India for the first leg of his Asia trip. He was forthright in criticizing Beijing for being “no friend to democracy, the rule of law, transparency nor to freedom of navigation.” His words prompted sharp retorts from the Chinese Embassy situated in New Delhi, that accused the US of “making pretexts for maintaining its global hegemony and containing China’s development,” by constantly stressing on the “so-called China threat,” and progressing towards establishing the vitality of its Indo-Pacific strategy.

Pompeo, during his India visit held a 2+2 ministerial meeting with the Minister of External Affairs, Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, which resulted in the signing of the Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement for Geo-Spatial Cooperation (BECA), a geospatial agreement that allows for the sharing of satellite data in real time and ensures the exchange of classified, incredibly sensitive information between the nations. The main advantage for the South Asian giant would be that it would gain an access to the highly-accurate US satellites. The document is one of the four core agreements that the US signs with its defense allies, as the other three have already been inked by the two nations in the past.

In this regard, Nepal Army’s retired Major General Dr. Purna Bahadur Silwal has stated, in conversation with DC Nepal, that the document would enhance India’s fighting capabilities with regards to its current situation with China and Pakistan. He has deliberated that the agreement could serve as a pathway for India to buy more advanced American weaponry, and hinted that it could be a part of New Delhi’s wider economic interests.

He has also suggested towards the possibility of an arms race in the greater Indo-Pacific region, if the US continues to stress on the present line of its Taiwan policy. China has recently released its 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) for National Economic and Social Development and the Long-Range Objectives Through the Year 2035, that contains China’s desire to match the US military might by 2027.

Within these contemplations is the idea of the US intelligence agencies and the bureaucracy that views certain issues with the same lens regardless of the change in the Presidency, as Brigadier General (Retd.) Dilip Rayamajhi further cautioned, when speaking to DC Nepal, that the “US does not want” and would possibly never want “India and China to develop militarily, especially when controlling the seas.” The US has a vested maritime interest in the greater Indo-Pacific, and its interest hinges on it remaining a dominating force in the region.

It is, moreover, necessary to realize that the National Security Strategy of 2017 had determined that China and Russia have been “developing advanced weapons and capabilities,” that could pose a threat to the US’s national security and interests. In assessing the US policy towards South Asia and its extending influence in the region with the Indo-Pacific strategy, Rayamajhi has noted that activities such as the Malabar drills are directed towards “containing China.”

He has further explained that the US Presidents have in the past mostly either focused on interests or on issues during their term in the Oval Office. “Trump gave a lot of impetus to American interests, but not to issues,” he said. He has posited that Biden’s Presidency may be more issue-based in the future, and he might step into the global arena by re-entering the 2015 Paris climate accords, emphasizing on tackling the coronavirus pandemic, and keeping a heightened focus on the human rights issues in China concerning the Uyghur Muslims, with an obvious eye also on Hong Kong and Taiwan.

While many believe that Biden could take a more diplomatic approach and try to smooth out the economic ties, there is a looming concern that with Biden at the helm of the free world, a greater probe into reports of China’s human rights violations and its engagements within Hong Kong and Taiwan could possibly take place. With Chinese President Xi Jinping holding off his congratulatory call on Biden’s win, President Tsai was quick to send her congratulatory message via Twitter.

The Trump administration has been known for adopting a hard line in its bilateral relations with China, and that was clear in high-level visit of the US secretaries to India as well as Sri Lanka. The continuous reiteration within Quad platforms to counter China, and the global call issued to be guarded with regards to Chinese technological companies, may echo during the Biden Presidency as well, but perhaps not to the degree that Trump advocated in his stance against China.

Nepal’s geopolitical scenario

Nepal has strongly expressed its commitment to the BRI. The Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) with the US is caught in a loop due to the requirement of the parliamentary ratification. Therefore, such a geopolitical dilemma would affect a small and landlocked state like Nepal. Silwal has commented that there will be implications in the case of tensions flaring at either ends of Nepal’s complex associations, especially considering India’s reluctance in the past in accepting China’s involvement in Nepal, and the wariness it exhibited concerning the US presence when relations between New Delhi and Washington were not so strategically aligned.

Observing Nepal in isolation would be impossible where the US is concerned. On the issue of Nepal’s presence in the contemporary age, Rayamajhi has mentioned “Nepal’s foreign policy has been dominated by the Indian politics,” that goes beyond the Indian Prime Minister and the ruling parties, but is contingent on its bureaucracy and agencies such as the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW).

Moving forward from the age-old rhetoric of Nepal being a “yam between two boulders,” he stated that the nation was constrained within the “shackle of geography.” He has argued that Nepal needs to shift towards “multi-alignment.” He has further posited that Nepal cannot be too close or too far from its Northern neighbor as China’s involvements are likely to increase due to Tibet and the fact that the mountainous terrains that served as a physical barrier before for China’s territorial security are now easy to traverse.

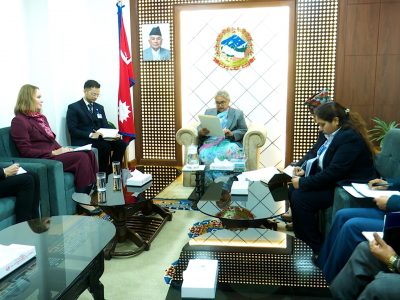

Former Foreign Minister Ramesh Nath Pandey, talking to DC Nepal, has pointed out that the US and Nepal had established diplomatic relations before India had even become an independent state. Though, in a period where Nepal’s importance has lessened in the global politics, he claims that the latter’s ability to achieve its foreign policy agendas is dependent on its own diplomatic capabilities, and the government’s competences.

He claimed that the US-India relations developed since the time that the US assisted India during the 1962 Sino-India war, at a time when India’s old ally, Russia, could not help the country. Following the end of the Cold War and at the turn of the new century, he has noted that the US monopoly has declined, as China has emerged as a great power, with India also joining the race.

A Biden Presidency is expected to affect the India-China dynamics, and with it, South Asia. Nepal’s geopolitical position is the determining factor for its foreign policy since it relies on its neighbors for transit and trade, as well as regional stability and peace. Experts have agreed on the fact that Nepal needs to iron out a clear foreign policy agenda, as Silwal has noted that “we are stuck” with the MCC and BRI and on the ways to take these initiatives ahead, because “beyond the black and white print, Nepal’s foreign policy is not really moving forward.”

The power structures would undoubtedly shift within South Asia, and within the greater Indo-Pacific with a new US President who has been claiming that he will be reversing quite a number of his predecessor’s policies. The extent to which Nepal can achieve its national interests, would be entirely dependent on the government’s ability to recognize the international developments, and devise as well as enact clear foreign policy objectives.

Facebook Comment

latest Video

Trending News

- This Week

- This Month