The Tragic Story of Nepal’s First Power House: From Dream Project to Neglected Museum (Photo Story)

In the year 1878 AD, humanity witnessed the birth of its first hydropower electric plant. Twenty-nine years later, Nepal’s Prime Minister, Maharaja Chandra Shumsher JBR, set out on a voyage to England to learn the secrets of harnessing the power of flowing water. After two months of intense study, he returned to Nepal with a steadfast determination to bring this revolutionary technology to his country and illuminate his palaces with the brilliance of electricity.

The Four-Year Journey from 1907 to 1911 AD

Upon his return to Kathmandu, in 1907 AD, Chandra Shumsher formed a committee under the special supervision of General Padma Shumsher JBR. For the next four years, the committee worked on building Nepal’s first hydroelectric plant, which would be located 12 kilometers south of Kathmandu, right below the steep hill of Sokhel in Pharping.

Executive engineer of the committee, Colonel Kishor Narasingh Rana, and Superintending engineer Colonel Kumar Narsingh Rana were responsible for planning the whole project in 324 Ropanis (16.5 hectares) of land. An English electrical engineer Barnau Puwante was hired to design the power station and perform the cost estimation.

The machinery required for the project, including turbines, generators, switchboards, control instruments, penstocks, and transformers, was gifted by the UK government under the Colombo plan. General Padma Shumsher JBR and General Keshav Shumsher JBR of the Nepali Army were in charge of transporting the equipment via the London-Calcutta-Bhimphedi route. The cost of transporting all equipment from London to Pharping in 1907 AD, was around 1 lakh 9 thousand rupees.

Reservoir: A Challenging Task

The construction of the reservoir at Pharping was a major engineering feat. Excavating an 18-foot-deep reservoir at the top of a steep hill was no small task, and required careful planning and execution. To ensure the safety and stability of the reservoir, it was surrounded by waterproof-treated concrete walls, which were built to withstand the pressure of the stored water and prevent any leakage.

The reservoir was an impressive structure, with a diameter of 200 feet and a full capacity of storing 15 million liters of water. It was strategically located near two natural sources of water, Satmule and Sesh Narayan, which provided a consistent supply of water for the hydropower project. This ensured that the reservoir was always well-stocked with water, enabling the generation of electricity.

Large and heavy penstock pipes with an inner diameter of 20 inches were laid over a distance of 0.7 kilometers on the steep hill, connecting the reservoir to the powerhouse. The fixing of penstock pipes was carried out by the Nepali army personnel, under the leadership of Colonel Tilbikram and Sergeant Bakhat Bahadur. The reservoir and pipeline installation both cost close to two lakh rupees.

500kW Powerhouse

At the base of the steep hill, a beautiful building was erected in Victorian architecture style. Electrical engineer Mr. Linzale from General Electric Corporation was invited to oversee the installation of all the equipment.

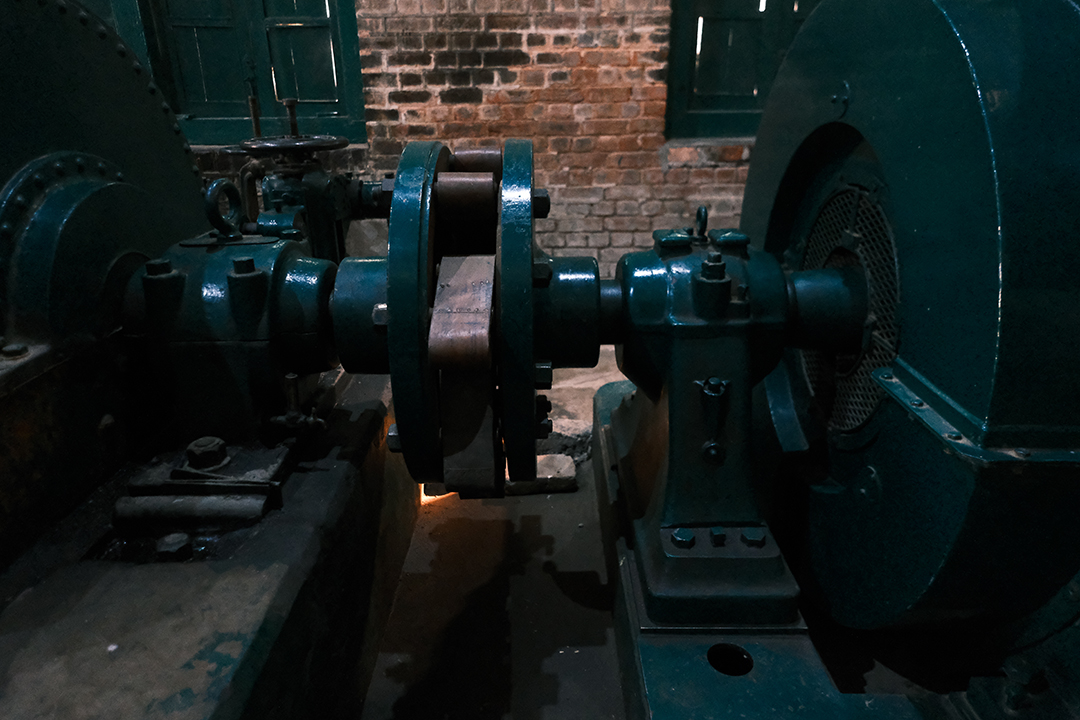

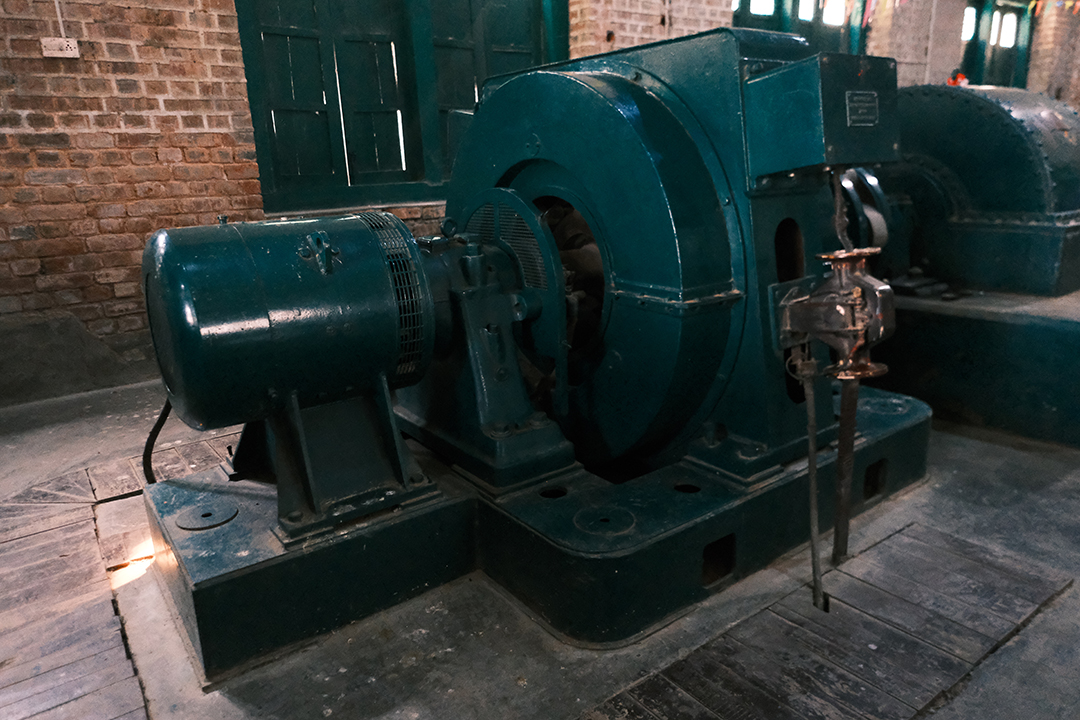

The main hall was dedicated solely to power generation, and it housed two Pelton Wheel Turbines, which were manufactured by an American company and had twelve buckets each. The water that arrived at high speed through the penstock passed through a specialized nozzle, striking the turbine buckets with great force, causing the turbine wheel to rotate at the speed of 600 rotations per minute. Each turbine was connected to an AC generator. Both generators had the ability to produce an electric current of 250 kW.

The 500kW electric current produced by the generators was then sent to a step-up transformer, installed in a separate room “Switch Yard”. The step-up transformer amplified the voltage of the electric current, allowing for transmission to Kathmandu. A 6-mile-long transmission line was established, with the support of sturdy wooden and metal poles. All of the construction works related to the transmission line were led by Lieutenant Devi Bahadur and Sargeant Harsa Bahadur.

After enduring four years of challenges, the power station was finally completed and ready to generate electricity.

1911 – Testing and Inaguration of Chandra Jyoti Vidhyut Griha

In the first week of May 1911, the powerhouse produced the first spark of electric current. The historic moment was marked by testing the current on a local resident’s house in the nearby Khokana village, located approximately 2 kilometers from the power station. The community gathered around Siddhi Lal Maharjan’s house in amazement as they witnessed glowing light bulbs, something they had never seen before.

On the evening of May 22, 1911, the then King of Nepal, Prithvi Bir Bikram Shah Dev inaugurated the powerhouse, by lighting a bulb in Tundikhel ground. The grand ceremony was attended by members of the royal family, the Rana clan, and some other high-ranking government officials. The day was officially designated “National Energy Day.”

The visionary behind the project, Prime Minister Chandra Shumsher, proudly announced during the ceremony that it was the beginning of a new era. “With the grace of God, our nation’s power plant will now provide us with illumination. This is Nepal’s first factory of its kind.” He also christened the station “Chandra Jyoti Vidhyut Griha” in honor of his own name.

Chandra Vidhyut Griha’s establishment marked a moment of pride as it became Asia’s second hydropower station, with the British Raj having constructed the first one in Darjeeling, India. One year after Chandra Jyoti’s inauguration, China had its first experience with electricity in 1912 AD.

Following Decades

Till 1951, the Chandra Jyoti powerhouse was a source of pride and prosperity for the ruling Rana. The power generated from the facility was mainly supplied to the palaces of royal elites.

However, the fall of the Rana regime in 1951 marked a turning point for the power plant. It was then decided that the electricity generated by the Chandra Jyoti powerhouse should be supplied to the general public in the Kathmandu valley. The powerhouse was also renamed “Pharping Hydropower Station.”

In 1982, the Government of Nepal commissioned a new hydropower project, the Kulekhani 1, with a capacity of 60 Megawatt. This new facility could provide a sufficient amount of electricity to meet the increasing demands of the population at that time. The 0.5-megawatt Pharping plant was no longer a valuable asset.

Shortly after the inauguration of Kulekhani One, the Kathmandu valley was hit by a drinking water crisis. In response, the reservoir of the Pharping hydropower plant was repurposed as a water storage and supply facility for the settlements in Lalitpur, including Patan. This marked the end of an era for the country’s first hydropower project.

Dead but A…Live Museum

In 2006, following a 25-year shutdown, the electricity authority initiated a maintenance campaign that involved cleaning, repairing, and testing the turbines, governors, control panels, control and protection circuits, transformer, and DC-supply system on local loads. The power station was found to be in good working order.

Five years later, in 2011, the Nepali government celebrated the plant’s centenary and erected a centenary monument in honor of the occasion. During the celebration, President Ram Baran Yadav declared the power station a “living museum” and since then, the machines have been frequently started to keep them in operational condition.

Despite being declared a living museum and a historic site, the first hydropower plant in Nepal has not received the attention and care it deserves. The neglect is evident in the deteriorating state of the architectural structures, with visible cracks appearing on the walls and ceilings. Additionally, land encroachment by locals has become a major issue, further compromising the integrity of the site.

Moreover, the park and monument, which was constructed to celebrate the centenary of the power station, lacks even basic facilities such as a toilet and resting/sitting spaces for the visitors. It is disheartening to see the country’s first hydropower plant, which once played a crucial role in shaping the nation’s energy history, now decaying and corroding as a result of a lack of attention and care.

It is imperative that the government takes immediate action to preserve and protect the historic hydropower plant. The country’s first hydropower plant should not be forgotten, and it is the responsibility of the government and the people of Nepal to ensure that the legacy of the country’s first hydropower plant lives on for generations to come.

Written and Photographed by Simon Paudel, DC Nepal. Special gratitude to Rajesh Shrestha, a diligent caretaker at the Pharping Museum.

Facebook Comment

latest Video

Trending News

- This Week

- This Month